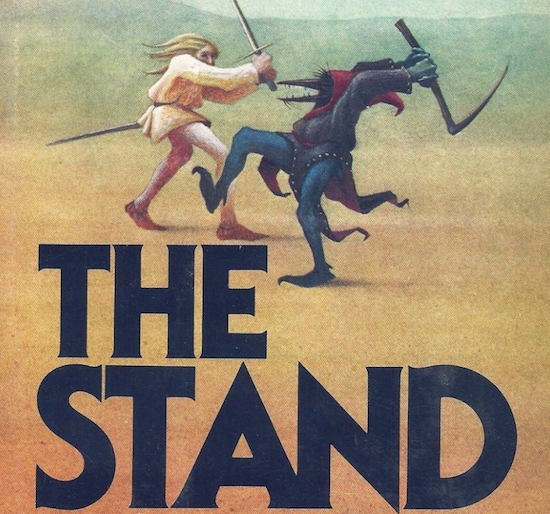

I’ve long had The Stand on my to-read list but only recently put the time into reading it. It’s infamously long and earns every bit of that opinion. I’d actually false-started on the book several times before over the years but for some reason, it was hard to get through. Maybe because the beginning didn’t immediately grab me and knowing how long it was, I had trouble reconciling the time it would take to read. But I’m constantly reminded by so many friends that The Stand is one of their all-time favorite books and so I knew I had to make it a priority and read it.

Anyway, I FINALLY made it through this past week and what struck me most (at least from a writer’s perspective) was how many common writing rules Stephen King breaks. I’m talking about the rules that you hear trumpeted on nearly every writing, agent, publisher, and author guru blog. Nearly every tip every tweeted with the #writetip hashtag is broken at least once in The Stand.

But here’s the crazy thing, a lot of this rule-breaking works (some of it doesn’t though – more on that as well). There’s a clear inciting event but the character’s goals are murky and meandering at best in many cases. There’s great characterizations but long info-dumps of backstory and asides that completely take the story off the rails for whole chapters.

All of that being said, the book is intensely interesting at times and filled with amazingly detailed and compelling characters that feel “real”.

After reading The Stand though, I’ve started to question some of the advice that constantly gets thrown at experienced writers (not new writers – because they should absolutely follow a lot of the common advice). I still believe the old adage:

“As a writer, you need to first learn and follow the rules before you can break the rules.”

But I’m wondering how so many of these rules can be broken and still work. Here’s a quick list of some of the common writing rules King broke in The Stand:

Backstory – Nearly every time a new character is introduced into the story, King stops everything to give a highly involved backstory of the character. He goes through their history, their personality ticks, thoughts, etc. It’s the ultimate in “tell” not “show”.

Info dump – Many times characters will encounter a new town or some new device or object and instead of the characters learning through the story more about this place or thing, King will just stop and give a multi-page history of the town or analysis of the object.

Character goal – Besides “survival”, there isn’t much else the main characters are working towards. Their goals meander among different options over time never really becoming clear until two-thirds of the way through the book.

Multiple protagonists – The general rule is to have one main POV character that at least 60% of the story happens in their head. But with The Stand, the story jumps around between all kinds of different characters, many times, even creating a new character, telling an involved backstory of them, and then killing them all in one chapter.

Omniscient narrator – POV is constantly broken by the narrator in the story. We will be in the character’s head, going along, then suddenly hear the thoughts of a different character in the scene, then back to the other character, then the narrator will give us some backstory on the place the characters are in that they would never know about on their own, then the narrator will hint at something to come in the story or make a comment about the situation.

Deus Ex Machina – The common advice is to make sure your protagonist’s choices are driving the story. That they are acting instead of being acted upon. But many of the major plot developments are acts of nature, circumstance, coincidence, etc. In The Stand, it’s almost as if the characters are pawns on a giant chessboard and an unseen hand is constantly repositioning them against their free will.

But what’s amazing to me is how many of these deviations from common writing advice work in the context of the book. And it’s not even that it’s a great story, the most important factor is the characters. They are so richly defined, flawed and yet intensely interesting. The other thing that is just staggering is the turns of phrases and similes that King is able to weave into the prose. In the end, those are the things I’ll most remember about the book and while it might not be my all-time favorite or anything, I can at least understand why the book is so beloved by a large group of people.